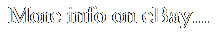

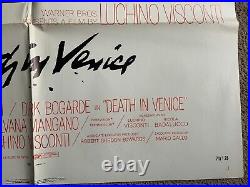

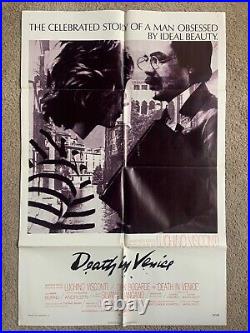

1971 Death in Venice WINNER Grand Prix Award Cannes 1 Sheet Movie Poster

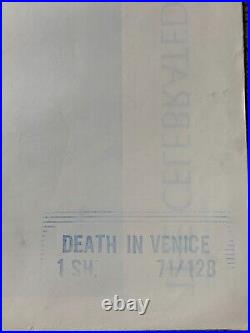

Venice (WINNER Grand Prix Award Cannes 1971). Morte a Venezia is a 1971 historical drama. Film directed and produced by Italian filmmaker Luchino Visconti. And adapted by Visconti and Nicola Badalucco.

From the 1912 novella of the same name. By German author Thomas Mann. As Gustav von Aschenbach and Björn Andrésen. As Tadzio, with supporting roles played by Mark Burns.

And was filmed in Technicolor. The soundtrack consists of selections from Gustav Mahler. Symphonies, but characters in the film also perform pieces by Franz Lehár.

(1969) and followed by Ludwig. (1973), the film is the second part of Visconti's thematic "German Trilogy". The film premiered in London. On 1 March 1971, and was entered into the 24th Cannes Film Festival.

It received positive reviews from critics and won several accolades, including, at the 25th British Academy Film Awards. The awards for Best Cinematography. In addition to nominations for Best Film. And Best Actor in a Leading Role. For his work on the film, Visconti won the David di Donatello Award for Best Director.

Retrospectively, Death in Venice was ranked the 235th greatest film of all time in the 2012 Sight & Sound. Critics' poll, the 14th greatest arthouse film. Of all time by The Guardian. In 2010, and the 27th greatest LGBT. Film of all time in a 2016 poll by the British Film Institute.Composer Gustav von Aschenbach travels to Venice. For rest, due to serious health concerns. Aschenbach takes quarters in the beachside Grand Hotel des Bains. While awaiting dinner in the hotel's lobby, he notices a group of young Poles.

With their governess and mother, and becomes spellbound by the handsome boy Tadzio, whose casual dress and demeanor distinguishes him from his modest sisters. Tadzio's image causes Aschenbach to recall an increasingly emotional and heated conversation with his friend and student Alfred, in which they question whether beauty is created artistically or naturally, and if beauty, as a natural phenomenon, is superior to art. In the following days, Aschenbach observes Tadzio playing and bathing.When he manages to get close to the boy in the hotel's elevator, Tadzio seems to throw a lascivious look at Aschenbach while exiting the lift. Returning to his room in an agitated state, Aschenbach remembers a particularly personal argument with Alfred, and he hesitantly decides to leave Venice.

However, when his luggage is misplaced at the train station, he is relieved and delighted at the prospect of returning to the hotel in order to be near Tadzio again. Before his return, he sees an emaciated man collapse in the station concourse, and, when he attempts to investigate this, the flattering hotel manager speaks in a dismissive matter of exaggerated scandals in the foreign press. Aschenbach adopts Tadzio as an artistic muse, but fails to master his passion for him and frequently loses himself in daydreams of the unattainable boy.

When a travel agent on Saint Mark's Square. Hesitantly reports to Aschenbach that a cholera.Epidemic is sweeping through Venice, Aschenbach's attention falters and he fantasizes about warning Tadzio's mother of the danger while stroking her son's head. Aschenbach follows Tadzio and his family to St Mark's Basilica. Where he observes him praying. He gets a makeover from a chatty hairdresser, giving him a resemblance to the old man who had pestered him upon his arrival, and pursues Tadzio's family again, until he collapses near a well and bursts into a pained laughter.

Back in his hotel room, Aschenbach dreams of a disastrous performance in Munich and Alfred's accusations afterward. When Aschenbach learns that Tadzio's family will be leaving the hotel, he weakly makes his way to the nearly-deserted beach, where he watches with concern as Tadzio's game with an older boy degenerates into a wrestling match.

Upon recovering, Tadzio strolls away and wades into the sea to the enraptured tones of Mahler. He slowly turns and looks toward the dying Aschenbach, then raises his arm and points off into the distance. Aschenbach tries to rise, but collapses in his deck chair, dead.

As Alfred, Gustav's friend. As Frau von Aschenbach, Gustav's wife.

Sergio Garfagnoli as Jasiu, a Polish youth. Howard Nelson Rubien as an English tourist (uncredited). Bill Vanders as the stationmaster. In Mann's novella, the character of Aschenbach is an author, but, for the film, Visconti made him a composer. This allows the musical score, in particular the Adagietto.(which opens and closes the film) and sections from Mahler's Third Symphony. To represent Aschenbach's work. Apart from this change, and the addition of the scenes in which Aschenbach and a musician friend debate the degraded aesthetics. Of his music, the film is relatively faithful to the book.

From left to right: Luchino Visconti. In the second volume of his autobiography, Snakes and Ladders, Dirk Bogarde recounts how the film crew created his character's deathly white skin for the final scenes of the film, just as he dies. The makeup department tried various face paints and creams, but none were satisfactory, as they smeared. When a suitable cream was finally found and the scenes were shot, Bogarde recalls that his face began to burn terribly.

The tube of cream was located, and, written on the side, was: "Keep away from eyes and skin". The director had ignored this warning and had various members of the film crew test it out on small patches of their skin, before finally having it applied to Bogarde's face. In another volume of his memoirs, An Orderly Man, Bogarde relates that, after the finished film was screened for them by Visconti in Los Angeles, the Warner Bros. Executives wanted to write off the project, fearing it would be banned in the United States for obscenity because of its subject matter.

They eventually relented when a gala premiere was organized in London, with Elizabeth II. Attending, to gather funds for the sinking Italian city of Venice. Gave an interview to The Guardian. In which he expressed his dislike of the fame Death in Venice brought him and discussed how he sought to distance himself from the objectifying image he acquired by playing Tadzio.Almost all the crew were gay. The waiters at the club made me feel very uncomfortable. In 2021, Juno Films released The Most Beautiful Boy in the World. It premiered at the Sundance Film Festival. In a 1971 review of the film for The Guardian.

Wrote: It is a very slow, precise, and beautiful film... An immensely formidable achievement, engrossing in spite of any doubts. Photograph from the principal cinematography with Silvana Mangano (face not visible), Björn Andrésen, Luchino Visconti and Dirk Bogarde. Wrote: I think the thing that disappoints me most about Luchino Visconti's Death in Venice is its lack of ambiguity.Visconti has chosen to abandon the subtleties of the Thomas Mann novel and present us with a straightforward story of homosexual love, and although that's his privilege, I think he has missed the greatness of Mann's work somewhere along the way. Wrote in his study The Great Romantic Films (1974): Some shots of Björn Andrésen, the Tadzio of the film, could be extracted from the frame and hung on the walls of the Louvre. He stated that Tadzio does not represent just a pretty youngster as an object of perverted lust, but that novelist Mann and director-screenwriter Visconti intended him as a symbol of beauty in the realm of Michelangelo. The beauty that moved Dante.

To seek ultimate aesthetic catharsis. In the distant figure of Beatrice. In a 2003 review of the film for The Guardian, Peter Bradshaw. Hailed Dirk Bogarde's performance as one of the greatest of all time, concluding: "This is exalted film-making". Published Death in Venice: A Queer Film Classic, a critical analysis of the film, in 2011 as part of Arsenal Pulp Press.S Queer Film Classics series. On September 1, 2018, the film was screened at the. 75th Venice International Film Festival.

In the Venice Classics section. Released a remastered edition of the film on. And DVD on February 19, 2019.

This is a great VINTAGE ORIGINAL 1971 MOVIE POSTER.